by Ryoko Ando

Translated by Tazuko Arai

Ms. Satsuki Katsumi was the principal of Tominari elementary School in Date city, Fukushima at the time of the disaster. (Ms. Katsumi then served as the member of Date city Education Board. She currently lives in Fukushima city.)

Q: Please tell us about yourself at the time of the 1st Dialogue meeting.

Decontamination works [for Tominari elementary school] started in July 2011. I was supposed to retire [at the end of March 2011] but it was extended, and I was working for the Date city Education Board. So, I haven’t settled down yet.

I felt as if radioactive material was scattered all over the area. I recall the Dialogue started in November 2011. The first meeting was held in Fukushima city, at the Fukushima Prefectural Government Office. In the beginning, my presentation was kind of muddled. Later, it got gradually better.

At the time, the decontamination works at the Tominari elementary school was finally finished. Even after retiring, they frequently called me to the school. And I used to wonder about the decontamination works, how it was done and what it meant, etc. I participated in my first Dialogue in such a time. In those days, my focus was on listening [rather than giving a presentation].

Q: So, you were keen to listen to other people.

Because everything was new to everyone.

Q: That is true.

I remember there was a question from the audience about [radiation in] the paddy field. A young staff from the Ministry of Environment talked about an experimental method that was building a huge concrete box and burying it under the paddy field. He was saying this practice must be implemented widely. I remember this exchange vividly. This experiment using a concrete box to for decontamination. And the need to spread this method little by little. He said the box was huge, a few meters by a few meters.

Q: For what?

It was an experiment to decontaminate soil in the fields. The experiment required a huge box [the size of a paddy field]. Later on, deep-plowing method was introduced. But there was a different suggestion [at the time]. The young staff from the Ministry of Environment just explained the method in words, without showing any physical model. Hearing his explanation, I felt it was unrealistic. There are so many paddy fields, how can you implement this method at once?

Q: I have an impression that the 1st Dialogue had a more authoritative atmosphere, being held inside the Fukushima Prefectural Government building and with the Ministry of Environment staff present.

Yes, it had an authoritative feel. The residents have the tendency to rely on the authorities first. I think many municipalities in Fukushima were also present.

Mr. Takahiro Hanzawa was working for Date city at the time. He is retired and currently lives in Date City.

Q: How was the 1st Dialogue meeting like?

Jacques Lochard and Chris Clement (Scientific Secretary of ICRP) were present. The other [foreign] guests were not so different from the other Dialogues. The organizers lined up the tables to form a square. On one side sat the staff from the Fukushima Prefectural Government and on another side sat seven to eight participants from abroad. I sat on a side together with Ms. Katsumi and Mr. Nonaka from Co-op Fukushima, etc. Each participant spoke about his/her experience at the meeting.

Q: Did the 1st Dialogue have a higher ratio of participants from the authorities?

Yes, it was high. There were participants from the central government, like the Cabinet Office. They explained the current situation and future plans. Jacques Lochard spoke about his experience in Belarus, etc. It was all new to me, and I just sat listening. I heard they had a meeting called the Dialogue in Belarus, but that was all. I did not expect the meeting to continue.

The media, both print and broadcast, were at the 1st Dialogue meeting, too. But I don’t think they spoke in the roundtable. As I said, the participants each spoke about his/her experience and then took questions, if any. The participants from abroad were asked about what happened after Chernobyl. The meeting did not proceed in the style that was adopted from the 2nd Dialogue in which everyone was asked to contribute.

Q: So, the format of the Dialogue changed from the 2nd meeting?

Yes. I would say that the 1st Dialogue was just a regular meeting. It was a rare opportunity to hear from foreign guests. So, I just listened. Many types of people started to participate only after the 2nd Dialogue. The participants in the 1st Dialogue were people like Mr. Nonaka or me, who were involved in [rehabilitation] activities. May be the objective of that meeting was to create a venue to meet foreign guests. Then, the Dialogue started to introduce Mr. Lochard’s method.

Apparently, the 1st Dialogue was quite different from the subsequent Dialogues meetings. The word apparently was used because the author was not present in that meeting. The Dialogue adopted the format we refer to as “our Dialogue” from the 2nd and the subsequent meetings. What was the format like?

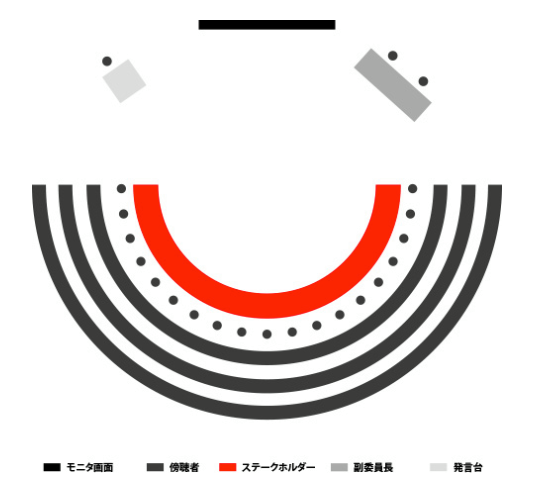

First, the organizers line up the tables in a square (sometimes a circle) in a room. This is referred to as the “roundtable.” The participants, at most 20 people, sit at the tables. The facilitator sits at one end of the square (or circle). What Mr. Hanzawa meant by “spoke in the roundtable,” was a process where each participant seated in the roundtable spoke in turn.

Outside the roundtable were chairs for the audience. The Dialogue meeting was in principle an open event(1), and any member of the public could attend the session free of charge, without prior reservation.

(1) The Miyakoji Dialogue held on March 12 and 13, 2016, was the only closed meeting.

Since the 1st meeting in November 2011, a total of 22 Dialogue meetings have been held in Fukushima. The first twelve were organized by ICRP, and these are referred to as “ICRP Dialogues”. From 2016, the residents and the local groups organized Dialogues for “Continuing the dialogue in cooperation with the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP).” Then, NPO Fukushima Dialogue was established and in 2019 which organized the 21st and 22nd Dialogue meetings.

The ICRP Dialogues were a two-day event. On both days, the morning session started with presentations, each about 15 minutes long. The presenters were wide ranging, from the experts and researchers, the staff from authorities, the teachers and the PTA, the farmers, the agricultural CO-OP members, those working for NPOs, and the residents of affected communities, etc. The ratio of the experts was higher among the presenters in the earlier meetings, and the local stakeholders increase over time. This was because in the early days after the accident, there was no data or knowledge about radiation and there was strong demand to learn expert knowledge on radiation.

In the afternoon session, the participants in the roundtable exchanged their opinions. This exchange is the essence of the Dialogue. About 12 to 20 people participated, both those who presented in the morning and those who came for the dialogue in the afternoon. Each took turn to express their opinions, following the facilitator’s direction.

The IDPA method described earlier, developed from the experience in Belarus, was used here. It is quite simple. The MC first asked a structural question, and each roundtable participant took turn to reply within a given time-limit. The limit was usually 3 minutes to 5 minutes. (It could be longer or shorter, depending on the Dialogue’s timeframe and the number of the participants, etc.) The participants were not allowed to interject while another participant was answering the question, whether it was a question or a comment. Thus, everyone had the same length of time to express his/her opinion without interruption. Conversely, all participants had to listen to their fellow participants’ reply quietly.

After all participants answered the structural question, (the first round), the facilitator passed the microphone around for a second round. Whereas the first round focused on giving his/her own answer to the question, the participants expressed comments and feelings after listening to the other participants’ answers in the first round.

In most Dialogue meetings, there were two rounds of questions. Occasionally, there were third rounds. If someone participated in both days of the Dialogue meeting, he/she had [at least] four opportunities to speak at the roundtable. (However, many participants only attended one day. If so, they would have spoken half the number of those who attended both days.)

Going back to the structural question, it was posed according to the four processes of IDPA method described below. For more complex issues, a whole day may be devoted to each process. But in the Dialogue, it was more simplified due to time constraint. On the first day of the Dialogue, the facilitator posed a question that combined the first and the second process. Similarly, a question combining the third and the fourth process was asked on the second day.

1. Questions for “Identification”:

- What is the nature of the problem?

- What are the challenges?

- What are the actors and entities concerned?

2. Questions for “Diagnosis”:

- What are the vulnerabilities and strengths of the situation?

- What actions have been implemented?

- How these actions have been assessed

3. Questions for “Perspective”:

- How the situation is likely to change over time?

- What are the challenges of tomorrow?

- What could be the negative, positive and the most likely scenarios?

4. Questions for “Actions”:

- What actions should be developed to avoid the negative scenario and favour the positive one?

- What should be done to change the situation?

- What should be the objectives?

Through this process, the roundtable allowed all participants to be treated equally in expressing his/her own opinion. They also had to listen to the other participants. Ms. Katsumi describes her experience as follows.

Ms.Katsumi : The microphone goes around and around, so no one can remain silent. I found the method intriguing. If you ask people to raise hands, only certain people will speak, and you only hear the same opinions. But by making everyone answer and assigning an equal time-limit, somehow everyone can speak up. If not for that method, I am sure some participants would not have spoken at all. It is important that all participants spoke. And by taking turns, someone will always point out something that you avoided.

Mr. Hanzawa spoke about his experience.

Mr.Hanzawa : Someone working for a city government (including myself) knows a lot about his/her city, but not about other municipalities. For example, Date city is in the middle part of Fukushima, so I was ignorant about the tsunami damages in Minamisoma city. Listening to those stories was very refreshing. There are quite many meetings organized by and for municipal governments. But the Dialogue taught me the importance of a meeting to share experiences in a broad sense. It allowed me to realize how we have been discussing some issues within the close and narrow relationship built in our area. I started to see the importance to get out of the box.

An important characteristic of this method is the listening part; each participant had to listen to all other participants.

After the accident, our society/community experienced a state of total chaos where people could not agree with each other nor share the same understanding. Even among close family members, you did not know what the other person was thinking. An environment where you could speak freely, your opinion was treated equally, and you did not have to worry about being interrupted was precious. And, expressing your opinion and learning those of the others in such environment was essential to grasp the situation people were thrown into.

Another strength of the Dialogue was that participants from different background/stance gathered together for the opportunity. It was not just the authorities and the experts, but also from the NPOs and the ‘ordinary’ residents. It allowed people to recognize that opinions/perspectives differed by their individual background/stance, and the reason why such differences came to be, without being emotional.

Participation of many foreign guests was also the Dialogue’s strength, including presentations from Belarus and Norway. Even if there was no foreign presenter, many experts from France, Canada, the United Kingdom, the United State, and other EU countries came to listen to the Dialogue and visit the affected areas. Questions/comments from the foreign guests often introduced a new perspective that helped us widen our periphery that tend to shrink out of wariness in the confusion after the accident.

As described earlier, the first twelve Dialogues were called “ICRP Dialogue Initiative.”

1, 福島原発事故による長期影響を受けた地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー チェルノビル事故の教訓と ICRP 勧告

2011年11月26日、27日 / 福島市

2, 第2回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 伊達市ダイアログセミナー

2012年2月25日、26日 / 伊達市

3, 第3回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 食品についての対話

2012年7月7日、8日 / 伊達市

4, 第4回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 子供と若者の教育についての対話

2012年 11月10日、11日 / 伊達市

5, 第5回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 「帰還―かえるのか、とどまるのか―」

2013年 2月2日、3日 / 伊達市

6, 第6回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 「飯舘―問題の認識と対応―」

2013年 7月6日、7日 / 福島市

7, 第7回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 「いわきと浜通りにおける自助活動-被災地でともに歩む」

2013年 11月30日、12月1日 / いわき市

8, 第 8 回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 「南相馬の現状と挑戦―被災地でともに歩む」

2014年 5月10日、11日 / 南相馬市

9, 第9回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 「福島で子どもを育む」

2014年 8月30日、31日 / 伊達市

10, 第10回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 「福島における伝統と文化の価値」

2014年 12月6日、7日 / 伊達市

11, 第11回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 「測定し、生活を取り戻す」

2015年 5月30日、31日 / 福島市

12, 第12回福島原発事故による長期影響地域の生活回復のためのダイアログセミナー 「Experience we have gained together(これまでの歩み、そしてこれから)」

2015年 9月12日、13日 / 伊達市

13, Miyakoji Dialogue

March 12-13, 2016 / Miyakoji, Tamura city

14, Iitate Follow-up Dialogue seminar “Sharing Experiences in Iitate Village Today”

July 9-10, 2016 / Iitate village

15, The Dialogue “The rehabilitation of living conditions in the Futaba region”

October 1-2, 2016 / Kawauchi village

16, Futaba-Ohkuma Dialogue Seminar

March 11-12, 2017 / Futaba town, Naraha town

17, What do we need for our future?

July 8-9, 2017 / Date city

18, Yamakiya Dialogue Seminar

November 25-26, 2017 / Yamakiya, Kawamana town

19, Odaka Dialogue Seminar

February 10-11, 2018 / Minamisoma city

20, Fukushima Dialogue “After Fukushima Nuclear accident: preserve memory, share experience and go toward the future”

December 15-16, 2018 / Iwaki city

21, Fukushima Dialogue “How far have Fukushima rehabilitation progressed? -in view of agriculture and fishery”

August 3-4, 2019 / Minamisoma city, Iwaki city

22, Fukushima Dialogue:Talking about the 9-year trajectory

December 14-15, 2019 / Fukushima city

The expenses for the first ten Dialogues were funded by the French Nuclear Safety Authority (ASN), Institut de radioprotection et de sûreté nucléaire (IRSN), Norwegian Radiation Protection Authority (NRPA), and The OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (OECD/NEA). These organizations have supported the programme to support the areas in Belarus affected by the Chernobyl accident in 1990s and 2000s. Their support for Fukushima was not limited to financial support. Staff from these organizations travelled to Fukushima to attend almost all Dialogues to listen to the voices in Fukushima and supported recovery efforts.

The Japan Foundation provided financial support for the 11th to 19th Dialogues. Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) became co-organizer for the 20th to 22nd Dialogues. We are also grateful for the various governmental grants for the 20th to 22nd Dialogues.

The Dialogue meetings were made possible through the support of numerous organizations and individuals that we cannot mention here. People from various backgrounds, including the residents in Fukushima, academics from Fukushima and elsewhere, those working for NPOs, have helped run the meetings. Most, if not all of them offered help pro bono. Especially the Fukushima Dialogue after 2016 were organized by different organizations and individuals each time. They proactively offered help to run the Dialogue. The people who organized each Dialogue changed every time. And, each Dialogue was supported by the organizers’ idea and capability and enthusiasm, as well as their human connection. It may be considered a miracle after a nuclear power accident that a gathering with such rich content could be held continuously over the years.

Now, let us consider what was discussed in the Dialogue meetings. It is impossible to describe the contents of all the meetings from 2011 until now. Thus, this summary will focus on the ICRP Dialogues from 2011 to 2015.

Next